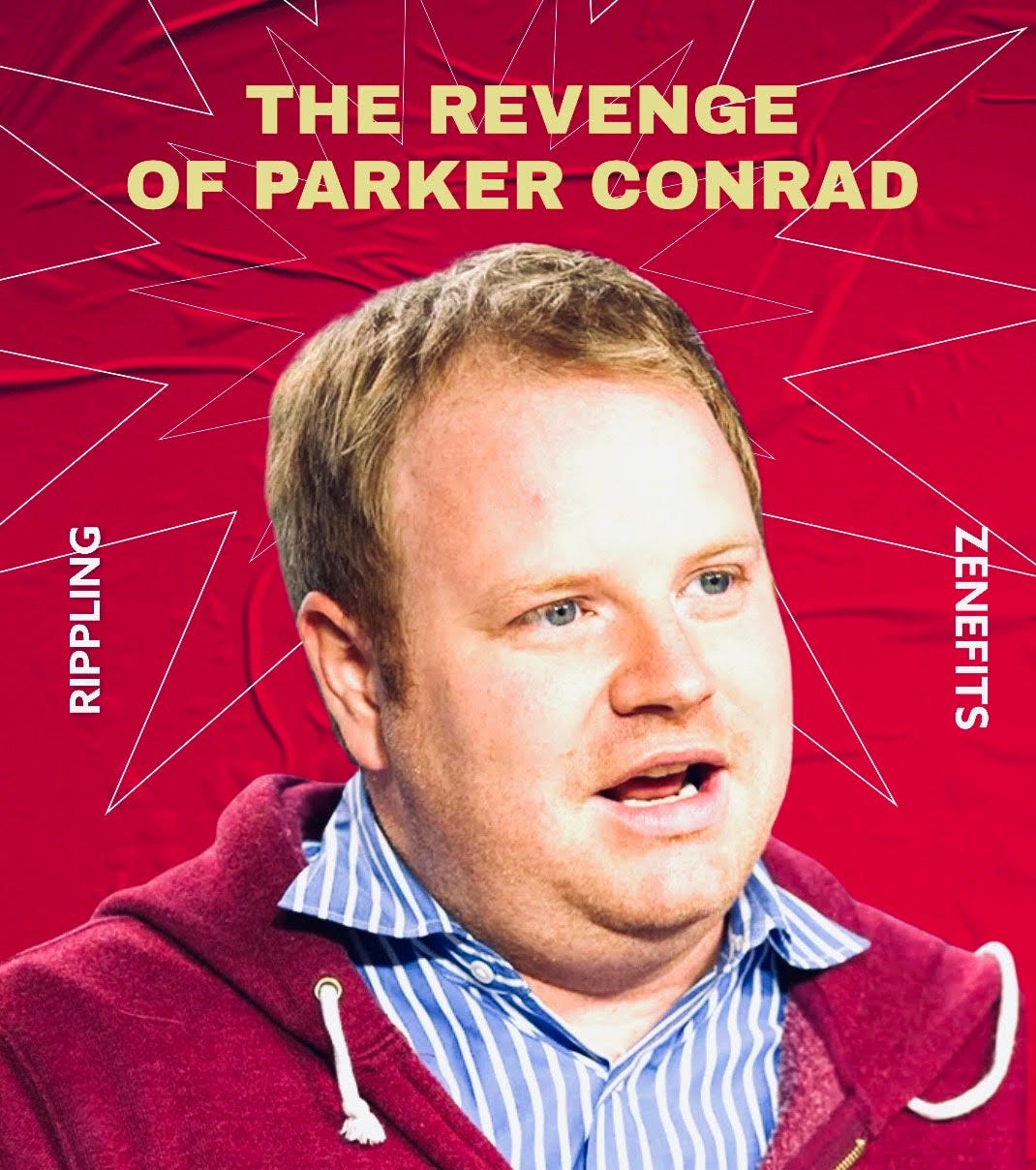

I recently listened to this excellent interview by Harry Stebbings with Parker Conrad, the CEO & Founder of Rippling. I found a few of his quotes to be tremendously insightful into his psychology and how he thinks about building an empiric company.

He views Rippling as the Phoenix that rises from his deposition at Zenefits: Creating his legend again, haunts him. Mentally he’s playing back the scenario, of what would happen if “I still ran Zenefits, if they gave me a shot versus the board deposing me what would i have done.” This boardroom scene drives him to make decisions he would have taken for granted had it not been for this cautionary tale. Arguably Rippling is more valuable and successful than Zenefits, so by removing the founder energy from the company, shareholder value was actually destroyed. These background regrets can spur even bigger ambition later.

Investors are General contractors not life partners: The episode at Rippling where David Sacks and Lars Daalgard deposed him shows that legal control of the board by a founder can be overriden by moral authority. Which is the biggest danger. The threat of investors, where they are happy to sue a company to force a founders hand to resign was the moral hazard at Zenefits. Sometimes the moral authority of a board member, in protecting his or her short term interests can handicap the company. The same can be argued at Uber, where the moral authority was really used by Benchmark’s partners to accelerate the IPO trajectory to force a liquidity event earlier. As such Parker is very cautious about big name investors, preferring a general contractor relationship versus a spouse construct.

Narrow thinking or ultra focus creates commoditization in SaaS: Parker argues with conviction that the earliest days of SaaS were about picking a niche and winning, and many billion dollar companies were created that way but the real value will accrue to the “compound startup”, which is cross selling many bundled products to the same user. At the SKU level, the compound startup can price lower, forcing focused startups to lose customers, and the bundled SKU level the compound startup can price higher. Also he argues that by having many things to bundle, a compound startup can have a more de-risked sales approach, because each SKU has a different buyer in the enterprise org, so if you don’t get through to the HR person, you can sell to IT, or accounting etc. The distinction he gives, which I agree with, is that the unifying value of a compound startup is a data model which can unify fragmented enterprise data and pipe it between different applications which form the bundle, so the network effect of adoption is acquiring the data asset, which then reduces the personalization time, and hence adoption time of other SKUs in the bundle, which ultimately translates to higher ACVs over time. I imagine this drives long term net revenue retention, which makes for a great investment. He cites salesforce as a canonical example unifying customer data into different applications, with CRM at the core to drive adoption of other salesforce SKUs. He views Rippling as the salesforce of employee data.

Big raises and geo-sourcing can create compound startups more easily now: Parker does not talk about his secret of having a large Bangalore engineering office as an offensive strategy, but he does mention that now it is possible to raise larger rounds than a few years ago, and with an excess of capital, compound ambition and geo-arbitrage can be a potent combination. UiPath’s recent $35B IPO shows what can happen when capital and geo-sourced engineering can be swiftly applied to take advantage of late mover advantage. I’ve written about this specific tactic here.

Share this post